Carbon is the sustainability metric that aligns with common discourse on climate change, from both investors and the general public. It helps organisations demonstrate that they’re committed to improving their environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance.

However, the reasons why our planet is in such bad shape goes further than carbon. Many businesses are narrowing their focus to decarbonisation at the expense of other sustainability imperatives.

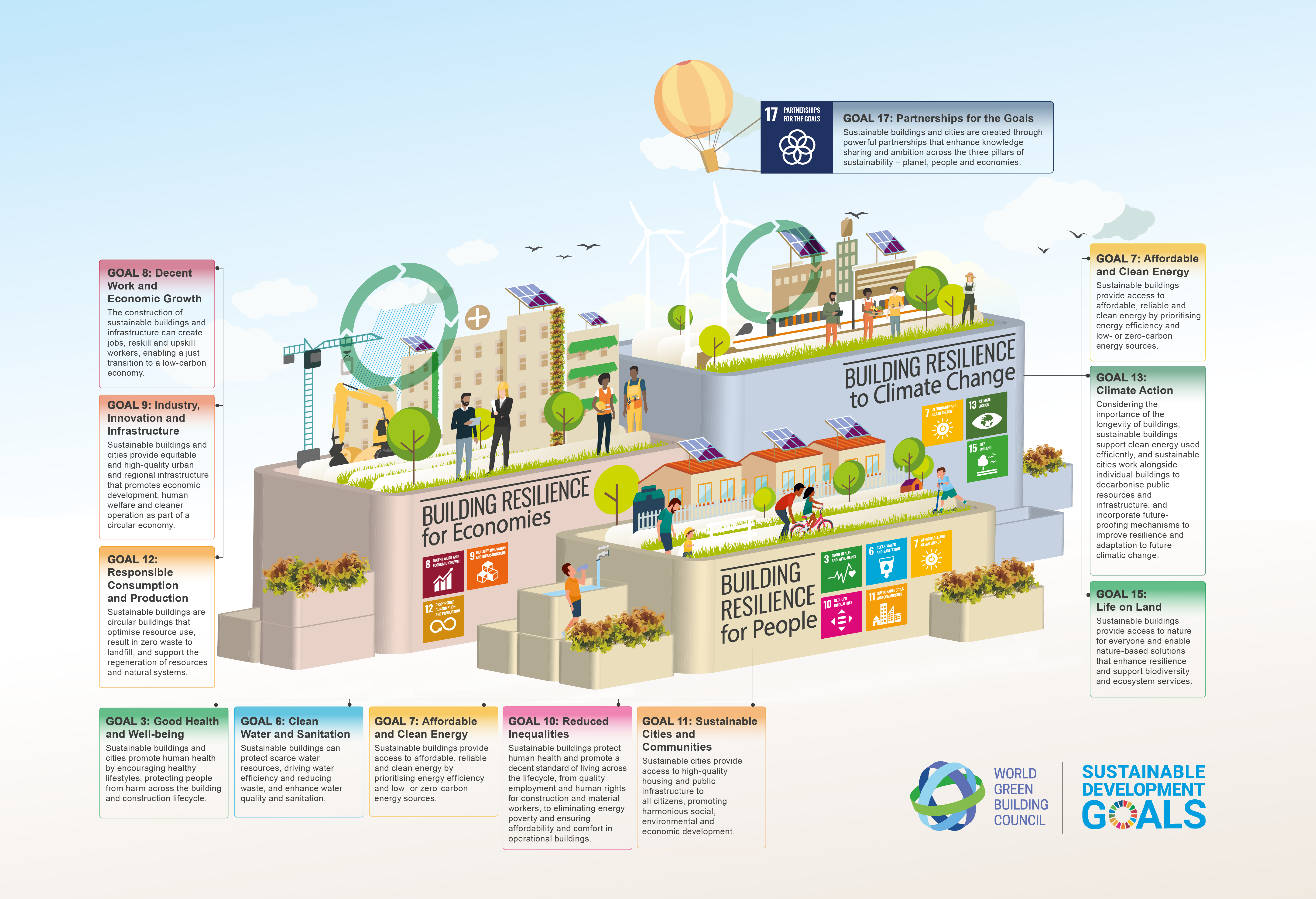

The United Nations provides a framework for members to work together to create peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future. At its heart are 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). They recognise that ending poverty and other deprivations must go hand-in-hand with strategies that improve health and education, reduce inequality and spur economic growth, all while tackling climate change and working to preserve our oceans and forests. Only 4 of the 17 SDGs directly relate to carbon (7, 11, 12 and 13). Many others are also relevant to the built environment.

By having a broad vision that touches other sustainability issues, as well as carbon, building services projects can create more value for their people, the planet and their bottom line.[1]

The contribution of buildings to the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals

Why carbon has become the dominant currency

There’s a global urgency to decarbonise

The growing scientific evidence and warnings about the climate emergency from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change led the majority of nations to ratify The Paris Agreement and commit to limit the increase in global average temperature to well below 2°C this century. This has fuelled a global urgency to rapidly decarbonise economic systems.

Carbon emmissions typically refer to carbon dioxide equivalents (CO2e), which include carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases (GHGs) like methane, nitrous oxide and hydrofluorocarbons. When released into the atmosphere, they create a greenhouse effect, warming the earth. The built environment is a significant contributor to climate change, responsible for almost 40 per cent of global GHGs. [3]

A number of tools and initiatives have been developed to help with decarbonisation. These include:

- green building certification systems, e.g. Green Star, BREEAM, LEED, NABERS

- legislation and government guidance, e.g. London Plan, New Zealand Government Building for Climate Change programme

- disclosure standards, e.g. the Task Force on Climate Related Financial Disclosure and recent International Sustainability Standards Board climate-related disclosures.

Saving carbon saves money and increases asset value

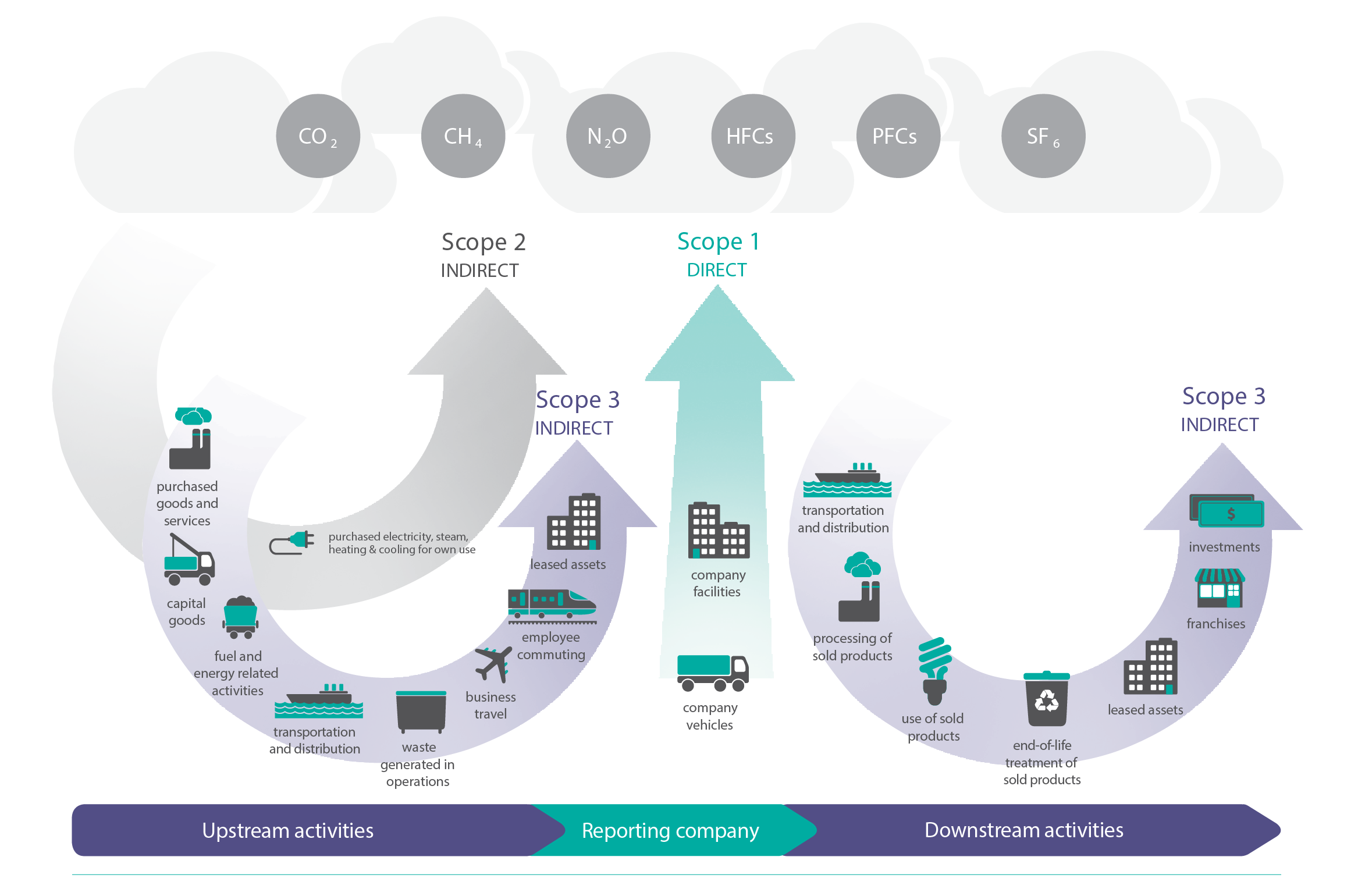

When companies reduce their GHGs, they become more efficient as they work to reduce their:

- scope 1 emissions: onsite gas or refrigerant leakage at company sites as well as petrol or diesel from company vehicles

- scope 2 emissions: consumption of non-renewable electricity at company sites

- scope 3 emissions: indirect emissions from their upstream and downstream activities, such as business travel or employee commuting, and transportation or use of their products.

Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions explained

Evidence of cost savings

- A recent study [4] demonstrated that, in Australia, there’s a green rental premium ranging from 2 to 8 per cent between the lowest rated and highest rated NABERS Energy buildings.

- Those with poor ratings face a 6 per cent rental discount.

- Buildings with a NABERS Energy rating of 5 or above also enjoy a 17.9 per cent premium on sales prices.[5]

- Further research suggests that 97 per cent of today’s commercial buildings aren’t zero-carbon ready and will face ‘brown discounts’ in the future. [6](A brown discount is the anticipated depreciation of buildings that aren’t sustainable as demand grows for ‘green’ buildings.)

It’s clear that energy efficiency measures reduce operational costs and decarbonising a building can increase sales and leasing value. This also helps investors avoid the risk of stranded assets that may result from future carbon legislation or carbon taxes and trading schemes.

The problem with a carbon only focus

Carbon targets can be misleading

There’s not enough industry data yet to have benchmarks and targets for whole-of-life carbon that adequately reflect unique building contexts, for example different typologies, uses, sizes, and geographies. As a result, setting targets is still open to broad interpretation.

While 500 to 600 kg of CO2 per m² is currently considered the appropriate target for for a new construction, often this blanket approach can over-generalise how a building should perform.

For example, a development may easily reach 450 kg of CO2 per m² if it retains parts of the structural frame. This is good performance in terms of the target, but the development very well may be overshooting CO2 per m² in other areas of the modernisation.

Additionally, if a building is a narrow high-rise or in an earthquake-prone region, the 500 to 600 kg per m² metric could be unrealistic. This doesn’t mean that the building’s design is wrong, it just means that the target isn’t appropriate. Additionally, the target isn’t taking into account other benefits of high-rise development such as densification and improved transport networks.

To sum up, the 500 to 600 kg benchmark may be appropriate for a new building under certain circumstances and not appropriate for a refurbishment.

It’s important we help our clients set realistic targets that are fit for the specification of their project, reduce carbon as much and often as possible and ensure the building remains commercially viable. This maximises its value both now and in the future.

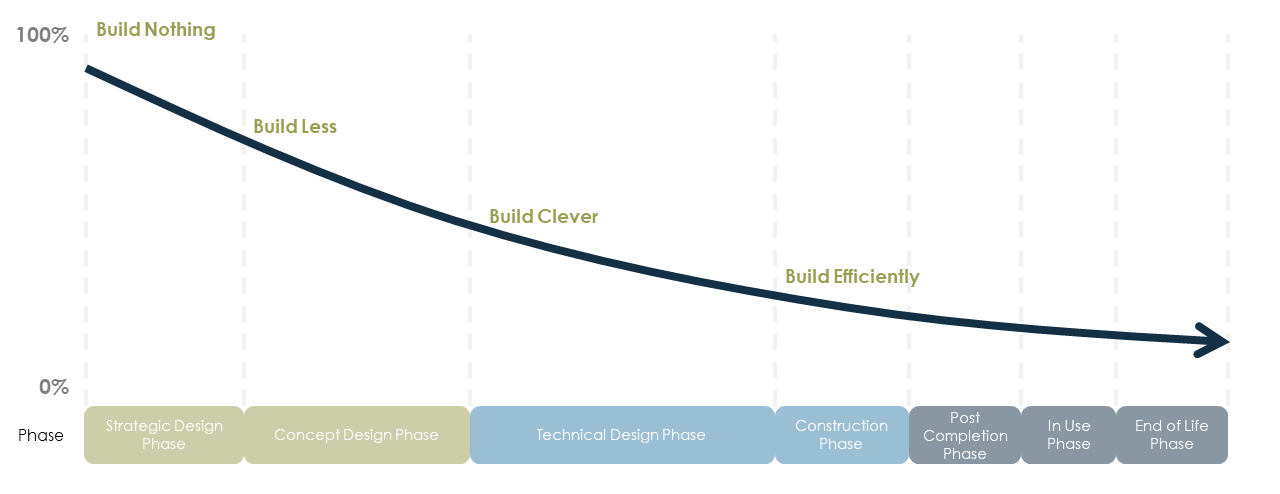

It’s also important to remember that the lowest carbon building is the one that’s already been built, so reducing and reusing in a build is key to reducing carbon emissions.

Building planning hierarchy

Carbon guidance is moving faster than project life cycles

Carbon has a whole life cycle and there are different parts that we can focus on to accurately measure emissions. In any build, it’s important to consider two distinct areas. The first is operational carbon. This is the easier type of carbon to quantify and relates to the emissions from a building’s operations, for example electricity, gas and water. The second is embodied carbon, for example the emissions associated with all the products and materials used in the building over its entire life cycle.

Usually, operational carbon is addressed with low-energy and high-efficiency design and equipment. In the built environment, we have standardised metrics and tools to monitor and analyse this type of carbon through NABERS. Utility bills and building management systems provide the necessary data to analyse operational carbon.

Embodied carbon is the new wave of carbon that’s trickier to quantify but is becoming increasingly important as operational carbon emissions decrease. One Green Building Council of Australia report estimates that embodied emmissions could represent up to 85% of Australia’s built environment emissions by 2050, rising from 16% in 2019.[7]

Across all markets, guidance is being put out and updated regularly on how to measure and assess embodied carbon emissions. As more assessments are completed and knowledge around embodied carbon assessments grow, each new guidance document that’s released significantly changes or adds to previous assumptions and methods recommended by earlier versions.

The increased regularity of these documents in the last few years has meant that the underlying principles of a whole-of-life carbon assessment completed on a building in 2021 will differ greatly from an updated assessment on the very same building in 2022.

This particularly applies to portions of the assessment like the in-use phase, where materials and products are replaced, maintained and repaired. Very little granularity of data exists around how often, and in what manner, products are replaced and maintained.

For many products, we’re still collecting data about this process and building on regional databases. For this reason, sustainability consultants measuring embodied carbon on the same project could end up with different results due to different measurements and assumptions on product emission factors.

We therefore recommend using carbon measurements as a decision-making tool rather than as definitive figures which calculate carbon over the long-term.

It’s worth noting that as operational carbon decreases with improved design, efficiency and equipment, the percentage of embodied carbon in a building will increase. However, through an active carbon reduction plan, the total carbon produced through operational and embodied carbon should get smaller year on year.

A focus on just carbon misses other important issues

People can get caught up in a carbon figure (the outcome) and stray from improving their way of working (the process). Let’s take the example of a whole-of-life cycle assessment, a tool which assesses the environmental impacts of products, processes, buildings or services through production, use and disposal.[8]

If you only look at the numbers in this assessment, you can reach the conclusion that you have a carbon intensive building. However, this assessment does not acknowledge that you may have provided the lowest carbon scheme for your development’s context, while optimising for other elements such as health, wellbeing, flexibility and other sustainability initiatives.

The results of an assessment like this should help with decision making but not be the only information used to shape a sustainability strategy. By simply aiming for a number, businesses can lose sight of what’s important to them.

- If a business just aims for net zero, it may forget to work on changing behaviour at source and make decisions that are detrimental to health and wellbeing or impact operational efficiency.

- When we focus on a single issue, other critical issues lose out even though they may be as important to our values as an organisation. Examples include improving air quality and procuring in a socially responsible way. A materiality assessment can help an organisation prioritise the social and environmental topics that matter most to them. This helps to set goals and introduce a balanced ESG strategy.

- Often, organisations could downsize their tenancy or encourage employees to choose a low-carbon commute to reduce their carbon impact. However, some of these actions have minimal impact on a carbon life cycle assessment and can be missed in favour of prioritising carbon offsets.

- Building projects can get hung up on a low-carbon materials for construction, for example sustainable concrete. However, this material may be limited in availability, could require transporting from overseas or make more of a difference if used in another industry. Often, looking at the bigger picture means going beyond your own organisation’s sustainability goals.

How to avoid Carbon tunnel vision

1. Set carbon as just one of your sustainability goals

One of your goals should be minimising carbon as you don’t want your building to risk being a stranded asset. However, it’s important to have a broader sustainability vision for your project that goes beyond carbon and addresses the more holistic UN Sustainable Development Goals. This will ensure an asset adds real value to customers, the community and planet. In some cases, it might be necessary to invest in materials that emit more carbon, in order to gain significant benefits in areas that you’ve defined as being of greater importance.

A specialist consultant can help create a sustainabliity vision for your project that also addresses issues like wellbeing, health, safety and on-site biodiversity, all of which are key to attracting tenants and maximising the value of an asset.

2. Use rating and accreditation tools to your advantage

By working with a sustainability specialist, projects can achieve a strong sustainable building rating like Green Star, BREEAM, WELL, LEED and Living Building Challenge.

These tools consider holistic sustainability initiatives and can help you see the bigger picture and achieve that broader vision. They can also become strong marketing tools that help attract higher rental and sales returns while helping minimise ongoing operational costs.

3. Allocate a carbon budget to your priority areas

By thinking of carbon as a currency, we can budget how we ‘spend’ it and ensure this spending fits within our wider sustainablity vision and priorities.

It’s important to understand how everything is connected in a building’s design and construction. By balancing business and ESG goals with project priorities, you can create space for carbon-costly initiatives. A laundry list of business and project priorities helps the development of a strategic carbon plan that forms part of a broader ESG strategy.

When buildings are developed with a broader understanding of sustainability in mind, they achieve carbon goals in a way that adds more value to owners, users and the community. They perform better overall.

Case study: Powered by nature – 435 Bourke Street, Melbourne, Australia

We’re working with leading national integrated property investor and developer, Cbus Property, on a new office project in Melbourne at 435 Bourke Street. Cbus Property is aiming to create a world-class commercial office tower that sets a new benchmark for sustainable office buildings.

Cbus Property has a vision which goes beyond just carbon by looking at all aspects of sustainability. It’s built a legacy of creating office, retail and residential buildings to the highest sustainability standards – ones which deliver positive environmental, social and economic outcomes.

Their focus for 435 Bourke Street includes environmental impact, wellness, connection to the community, nature and productivity.

The building will be one of the first office towers in the world to feature a façade integrated photovoltaic (PV) system. The integration of solar panels within the facade’s shading elements generates a portion of the base building’s electricity as well as reducing the air-conditioning loads.

The remainder of the all-electric building will be powered by renewable electricity and net zero carbon from the first day of operation. The design is also targeting:

- Green Star Buildings – 6 Star

- WELL Certified Core – Platinum

- NABERS Energy Base Building – 5.5 star with 6 star stretch target in operation

- NABERS Water Base Building – 4.5 star

- SmartScore – Platinum

- WiredScore – Platinum

435 Bourke Street will be a pioneer project for Australia, if not the world, and one that responds to the future of the workplace. It also supports Cbus Property’s aspiration to deliver the most sustainable buildings in Australia, if not the world.

Note: We acknowledge the rapidly evolving carbon landscape and associated guidance for best practice. This article is based on the knowledge we have to hand in August 2023.

[1]https://sdgs.un.org/goals

[2] https://ungc-production.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/attachments/cop_2022/506652/original/WorldGBC%20Annual%20Report%202021_LR.pdf?1641291230

[3] https://worldgbc.org/advancing-net-zero/embodied-carbon/

[4] https://www.cbre.com.au/insights/viewpoints/asia-pacific-viewpoint-the-green-building-premium-does-it-exist#:~:text=While%20the%20precise%20magnitude%20of,be%20willing%20to%20pay%20a

[5] https://mktgdocs.cbre.com/2299/96cfbd5f-9a51-4205-ac0c-c5707356648f-2084607075/APAC_The_20Green_20Building_20.pdf

[6] https://www.fidelityinternational.com/editorial/blog/how-big-a-threat-is-the-brown-discount-447270-en5/

[7] Green Building Council of Australia, Embodied Carbon & Embodied Energy in Australia’s Buildings, 2021 https://new.gbca.org.au/news/gbca-news/gbca-and-thinkstep-release-embodied-carbon-report/

[8] https://www.gdrc.org/uem/lca/lca-define.html