7 November 2016

Norman was born on January 24th, 1930 in a little farming town called Beverley in Western Australia. Located approximately 130 km east of Perth, Beverley was considered a rural outpost.

David Norman, founder of NDY, was a pioneer of the engineering consultancy industry in Australia. With a focus on service and communication, as well as innovative results, his methods proved well ahead of their time, and paved the way for NDY to prosper, and spread this approach across the globe.

The depression of the 1930s was hard on all farming communities across the country, and by 1936, Norman’s family was forced off their land. This disrupted David’s education and he subsequently did not commence his formal schooling education until eight years of age.

“I was well behind the rest of the class and it was a huge disadvantage,” says Norman. “We might have moved to the city, but with World War II breaking out, the family thought it would be best to stick together. My mother, Deborah (my sister) and I returned to Beverley at the beginning of 1942, and we attended the local school there.

“I’m indebted to the school because the two teachers I had did a fantastic job for me. They really put some effort into me and I responded, and within two years they got me up to be competitive with the rest of the group. That was a terrific relief to me and a huge boost to my self-confidence. After 1943 I went back to Hale school and completed my education there.”

By the end of high school, Norman had made two bold decisions; he wanted to be an engineer, and he wanted to start his own business.

Norman went on to study engineering at the University of Western Australia, where he managed to impress his Professor with his ingenuity.

“The Professor had this fan that he had been given out of a mining ventilation system. It wasn’t working very well, so the professor gave it to me to sort out, as my thesis for my final year.

“I set up the test rig and ran tests on the fan, which showed there was little air flow near the hub and considerable recirculation around the perimeter.

“A decision was made with the Professor to reduce the diameter of the fan to move the air flow closer to the hub and narrow the gap around the cowling to reduce the recirculation: this only increased the fan efficiency by a disappointing 7%. We then tried mounting straightening vanes behind the fan, this also produced a negligible improvement. But then I looked at the pre-whirl in front of the fan, which was significant and decided to add four vanes to try and straighten the airflow onto the blades. I also angled the vanes to move the airflow nearer the hub. To my amazement this took the fan from an efficiency rating of 37% to 55%.”

This innovative task, along with the emergence of air conditioning as an industry, inspired Norman to look at the career opportunities emerging within this growing field of engineering.

“Looking back with hindsight, I have been extremely lucky, the timing was ideal in that the air conditioning industry was in its infancy and that opened up all sorts of possibilities for me,” says Norman.

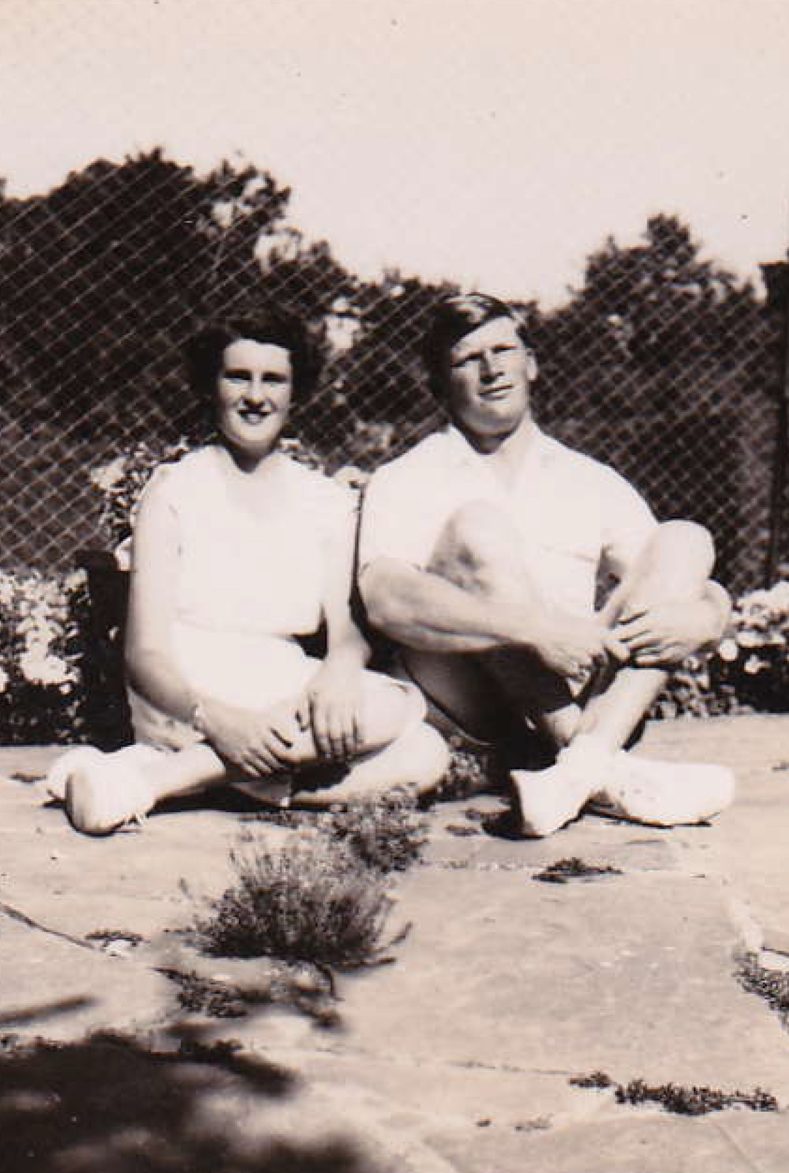

Norman family 1910

Seated: Constance Mary (Con), Colin Hugh Boyd (Hughie), Margaret Mary Norman, Hugh William (Bill).

Shortly after graduation, Norman noticed an ad for an air conditioning and ventilation engineer for the Commonwealth Department of Works in Adelaide. The recession was still weighing heavily on WA, so he chose to apply for the role, and was successful.

“I had been there about 3 months and was bored stiff. I was seriously looking for another job when the boss called me in one day and said ‘David you have been selected to go up to the Woomera Rocket Range to take over responsibility for the supervision of all work done in the mechanical services side on the range’. There was plenty going on at the range at the time, so I went,” says Norman.

There was indeed a lot happening at Woomera, with significant work being carried out on various projects. Norman was put in charge of two fiveman labour crews. “The foremen on both gangs thought I was just a ‘wet-behind-the-ears kid’. I also had to supervise all the outside contractors that were working on the range, as they were preparing for the British ‘Blue Streak’ rocket development,” says Norman “I had an excellent experience there and it reinforced to me that air conditioning was going to be a major industry.”

Norman had taken notice that air conditioning was becoming more accessible, and production of the necessary products was becoming more affordable too.

He decided to do whatever he could to get ahead of the industry, and get the best possible training and knowledge that he could find. He determined that Australia didn’t offer the expertise he needed, but discovered that the training was available in North America.

“I identified Carrier Corporation as the firm that offered the best training. I applied to go to America and work for them, but unfortunately there was an eight year waiting list.”

But Norman’s ambitions wouldn’t let him wait that long.

“With the industry moving so quickly, and with the Australian climate sure to create a demand for air conditioning, I looked into other options, and I found that Carrier had a branch office in Toronto, where their Canadian head office was, so I decided I’d go there.”

Norman arrived in Toronto in May, 1954, and his unique experience and natural ability as a problem solver created a demand for his services. “Carrier offered me a salary of $275 a month. Others were prepared to pay me over $400 but I stuck with Carrier because I was after the knowledge they had. That turned out to be the right choice in the long run.”

Norman spent three months designing air washers for a DuPont factory in Hamilton. Afterwards, he was seconded to the Supervision Division, where he spent the next two years putting in large plants all across Canada, from Winnipeg to Montreal. Each project had its own challenges, and Norman learned quickly what was necessary to have an efficient and reliable air conditioning plant.

Chris & David Norman – 1960

The Normans – L to R: Chris, Joanna (standing), Katharine (sitting on carpet), David, Suzannah, Jeniffer.

Norman’s ability to innovate in the fledgling industry of air conditioning was noticed by management, and earmarked for greater responsibility. Norman was transferred to the Design Section and promptly sent off to do a three month training course in Syracuse. “The course really took you through every aspect of their operation, from design right through to cost control and documentation. It was very comprehensive, and gave me all the basic information I needed to start my own operation,” says Norman.

Upon completion of the course, Norman returned to Toronto. He was responsible for several medium sized offices and a small number of industrial plants, before being placed in control of the Imperial Life Insurance building project. At the time, this was the largest building retrofit that had been done in Canada.

A unique challenge of this particular project was that the building had to remain operational during the retrofit. “They wanted to keep all the people in the building right through the entire project,” says Norman “this meant all the work had to be done at night and the office spotlessly cleaned the next morning to start. It was quite difficult, but we had good contractors and I learned valuable lessons from this project.”

The retrofit was successful, and the client was particularly pleased that the building was kept in use throughout the process, and gave Norman an excellent reference that he would later use in Australia to help establish his own company.

Norman’s ongoing success, innovation, and adaptability, saw him appointed as Engineer in Charge of the General Air Conditioning Division for Canada, an astounding achievement for someone so young, and recognition of his capability in a rapidly expanding industry.

Norman spent four-and-a-half years in Canada, but soon felt the need to return to Australia, and in 1959 he settled in Sydney.

He immediately began looking for jobs, but the post-war recession was still affecting the industry, making gainful employment difficult to find.

A meeting arranged through friends with the CEO of Westinghouse, Australia (one of the largest and most diverse companies in the world at the time) proved to be the turning point for Norman. He discussed his thoughts and plans with him, and he asked Norman whether there were any other areas in which he could start his business. Norman mentioned that consultancy in the building services area was a viable option, particularly with a specialisation in the burgeoning air conditioning sector that was sure to be a major growth market in Australia’s warm climate.

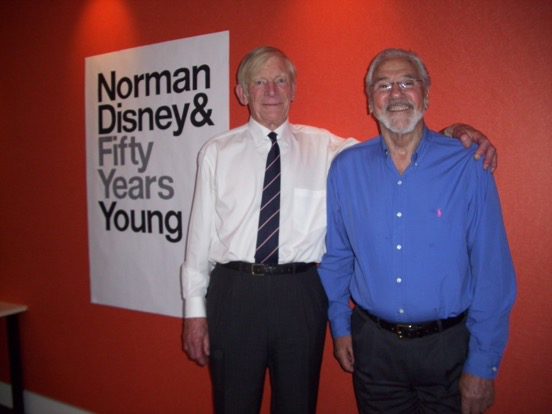

By early 1960, the workload necessitated adding a design draftsman, and Alan Disney came on board and according to Norman, Alan displayed significant initiative and an ability to manage clients as well as staff.

David Norman and Alan Disney in 2009

Norman subsequently spent time investigating the status of the market, by visiting architects, consultants, engineers and equipment installers to gauge how the market was behaving. The architects in particular expressed concerns that the quality of consulting in the mechanical services side was lacking. Norman repeated the process in Melbourne, with the same result.

Having identified the gap in the market, Norman proceeded to fill it. The climate of Sydney suited him better, so with that as the initial office, Norman set up his consultancy.

One of the first things he needed was a telephone. He was informed that this could take several months, which he found intolerable, however, if he had a government contract, it would be less than a week. He did exactly this, setting out to get a small government project approved. This satisfied the criteria, and got his telephone, and his first client at the same time as his new business cards arrived, boldly proclaiming his new venture as “HD Norman and Associates”.

Norman immediately set about cold calling as many architects and developers as he could, convincing anyone that he could to hire him, and spending the nights and weekends working on the projects that they contracted him to do. This continued for many months, as Norman sought to get his company into the consultancy list of as many businesses as possible.

The commitment soon paid off, with more work coming in than he could complete himself, he formed a partnership with Leo Addicoat in May, 1959, forming Norman & Addicoat (N&A).

Addicoat was responsible for the electrical, general mechanical and lifts while Norman focused on the air conditioning, ventilation and refrigeration aspects of the work. They soon moved into a bigger premises at 50 Miller Street in North Sydney, in the corner of the structural consultant’s office of Taylor Thompson and Whitting.

Norman continued aggressively pursuing work while Addicoat held down the drafting during the day, with spare moments few and far between for the both of them. By early 1960, the workload necessitated adding a design draftsman, and Alan Disney came on board and according to Norman, Alan displayed significant initiative and an ability to manage clients as well as staff.

“The volume of projects had dramatically increased, and with it we had to be selective in our choice of suppliers and installer,” says Norman. “It took some time to get the quality we wanted, but protecting the reputation of the business was a priority.”

Yet despite the momentum, it would be some time before the firm won any large projects.

“In hindsight, I think it was of enormous benefit to us, that we were not awarded a major project before then,” says Norman. “We needed the opportunity to iron out many industry equipment and installation problems on small plants and bed down our team before taking on a larger project. By focusing on smaller work, we were able to eliminate most of the major problems by the time we graduated to doing large work.”

Alan being a natural marketer actively worked with Norman to secure several projects and develop good clientele.

Initially, N&A worked on smaller projects, such as office blocks, bowling alleys and RSL clubs, but the big break for Norman and his company came in 1963. N&A won two major city contracts – Goldfields House project on McKee Street and also the Sydney County Council building at the corner of Bathurst and George Streets.

It’s a testament to Norman’s attention to quality and detail that there are many tall buildings designed in the 1960’s which remain fully operational to this day.

On a visit to family in Western Australia, Norman looked up an old school friend who was now a partner in the architectural practice of Forbes and Fitzharding. They had just been commissioned to design a new head office branch for the Bank of New Zealand (now the ANZ Bank). Norman secured the air conditioning contract, under the condition that N&A open a branch in Perth, which they did in 1964.

David Rae was tasked with managing the Perth office, a role that Norman considered exceptionally important.

“I was always very conscious that the quality of the Manager of the office would in many ways determine the success we had,” says Norman. “Right from the start, I had a number of young engineers who I kept directly under my mentorship, so I could monitor exactly what they were doing, and I usually found it took about three years to get the culture that I wanted stuck in their minds. It also allowed me to understand exactly what their ability was in design, in business development, in control of staff, in communication and financial control, plus handling of political situations and stress. That way when I sent them out, I knew what I had to look after and what I could rely on them doing and I considered myself pretty lucky, I could sleep soundly at night and was seldom let down.”

It’s a testament to Norman’s attention to quality and detail that there are many tall buildings designed in the 1960’s which remain fully operational to this day.

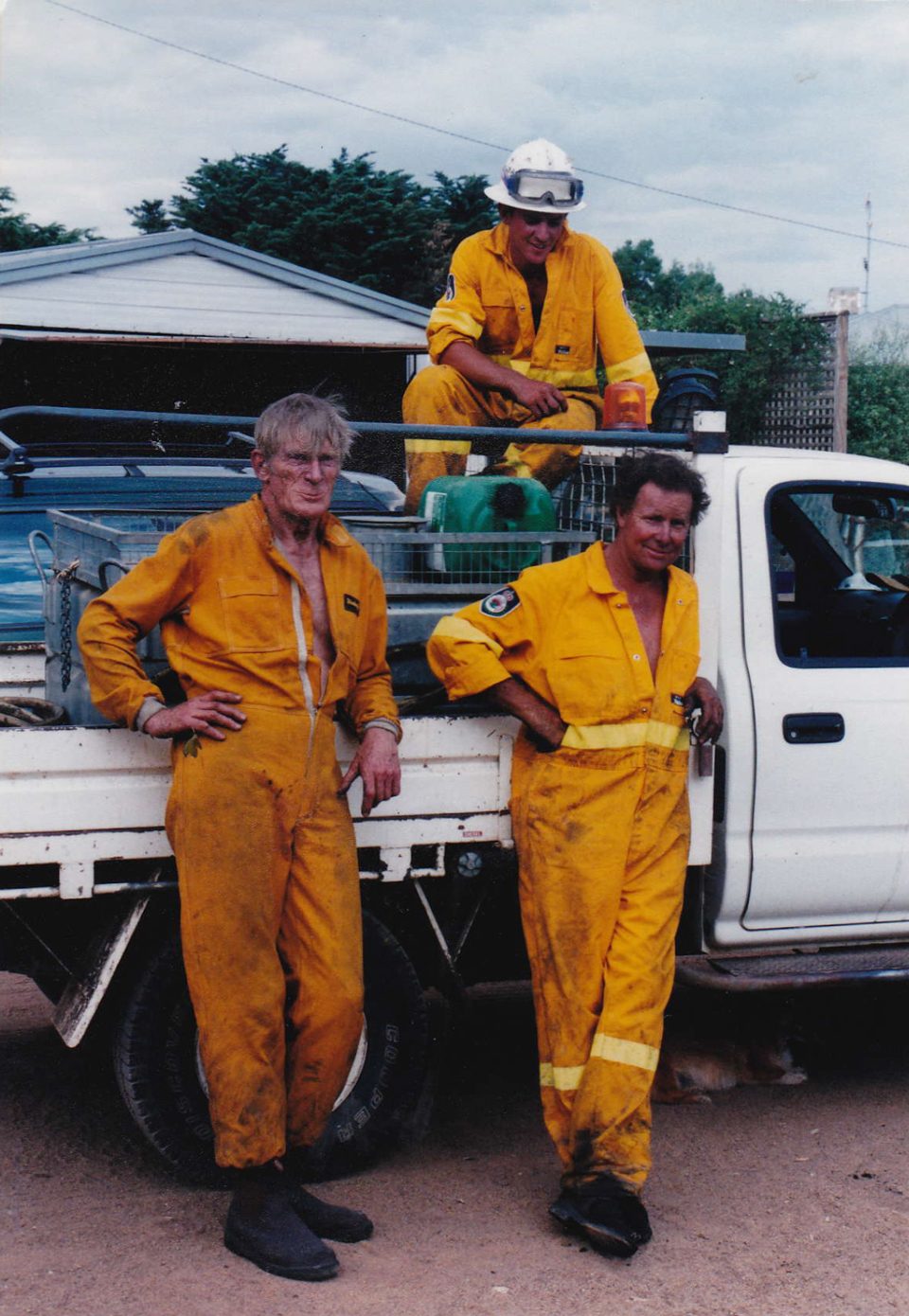

L – R: David, Anthony Brown (Farm Hand) and Tim Kelly (Farm Manager) after fighting bush fires on adjoining farmland in country NSW

Melbourne was the next target for expansion, and Peter Young was tasked with managing the new Victorian office. It took some time to gain momentum, due to the depressed economy and business climate. In 1971, Leo Addicoat and David Norman had differences of opinion on the direction and structure of the company. The result was that Norman & Addicoat was dissolved, with Addicoat taking control of the electrical, mechanical and vertical transportation contracts in Sydney, while Norman was left with the air conditioning, ventilation and refrigeration, along with the Perth and Melbourne offices, with a total of 85 staff.

The offspring from this business divorce was a new operation called NDY – reflecting the three principal partners.

Business continued, and in 1972, NDY opened up an office in Brisbane, immediately making an impact with a variety of work. The focus on client service had provided the firm with one of the most precious things a new business could have – a solid brand reputation.

NDY set itself at the forefront of the HVAC industry, pioneering an innovative low pressure reheat system for use in major buildings.

“Up until our entry, nearly all systems in major buildings were High Pressure double duct systems,” says Norman. “They were at least twice the price of the Low Pressure reheat system and used twice as much energy.”

“When High Pressure Variable Air Volume or VAV systems appeared we converted our Low Pressure reheat system to a Low Pressure VAV System with reheat. We then produced a system which had a Constant Volume supply serving the perimeter and designed to offset the transmission load at all times.

“This in effect placed an envelope around the building and looks after all heating requirements. The VAV system then only has to deal with heat buildup from sources such as the sun, lights, equipment, and the occupants themselves. This removed the need for heating coils on floors, and significantly reduced the amount of reheat required, which also reduced the maintenance requirements for the floors.

“This system was used in the NAB Building in George Street, Sydney and has operated at an energy usage of 165mj / sq m pa of net air conditioned area. This is a figure stated by the AMP, who owned the building and is the lowest claim I have heard of, for any major office block in Australia.“ Norman adds.

NDY was also responsible for setting quite a few standards over these formative years. “We took the attitude that whenever we came across anything that wasn’t working correctly, we did something about it to either make it less maintenance intensive or more efficient. For example, we were having trouble with the package air conditioning plants in smaller buildings. The bearings, belts and alloy pulleys were all failing far too frequently.

“We examined the problem and found the bearings were failing due to undersizing, or by being over greased. We fixed this by using heavier bearings with a grease relief valve housing. Then we found that the belts were undersized, so they’d slip on start up, and before long they’d give up the ghost. We fixed that by using heavier duty belts or alternatively multiple belts. For the pulleys, we changed from alloy to cast iron.”

These three solutions were at negligible cost, but the saving in maintenance was enormous. Instead of replacing belt drives and bearings every year, the drives on package units were able to last for five to eight years, and the belts on large fans were often lasting up to 15 years, providing significant cost savings for the building owners. This was a revelation in the industry.

I always believed that the CEO has to lead from the front. You set the agenda, you set the strategy, the aims, the ambitions that you’re looking for and your business is to make certain that others follow.

NDY’s growing reputation for innovation continued with the Energy Plant Management Division (EPM). This was an initiative taken by NDY in response to the difficulties in getting contractors to properly tune and commission the plants. Long delays were common, with contractors requiring frequent instruction or onsite supervision. Additionally, many plants were running inefficiently, so the opportunity to meet client demand was identified. The team was able to improve the speed of installation, as well as tune the plants to be more efficient, for new and existing buildings.

“Out of the top ten technicians in the field, we had about 5-6 of them,” says Norman. “They could go out and fix anything and they were true innovators.”

The other ‘industry first’ NDY conceived with its EPM team was in testing new equipment. Rather than purchasing new items in bulk and trusting that they would work as intended on a project, they could test small quantities, and then roll these out across all projects, with full confidence that they would work.

“By being able to implement our designs, we were able to offer more than our competitors. Being able to bring more to the table was a definite leg up,” according to Norman.

The early eighties marked the turning point for the company, with offices opened in Kuala Lumpur and Canberra in 1982. The new Parliament House provided a major opportunity for NDY to contribute to a high profile project with national interest.

“In 1982 we were awarded the new Canberra Parliament House to do the air conditioning, the Building Monitoring System, the sprinkler system and the beer plumbing. That was the biggest job we had ever done to that point.”

Shortly after, NDY opened an office in Adelaide, with quick success. This prompted an expansion into New Zealand, with offices in Auckland and Wellington. By 1989, NDY employed around 500 people.

Norman placed great emphasis on keeping every office autonomous, but with a strong culture and commitment to the rest of the company.

“I took the view that the Office Manager was totally responsible for his operation within fixed limits, and if he wanted to go outside those limits then that had to be referred back to me. I wanted the managers to trust their instincts, and we did have some fantastic people, but I needed to ensure that every office was taking the same approach.”

To address the culture and documentation challenges, Norman had a design manual developed. It specified how a system should be designed, how the system should be used, what suppliers were preferred, rates to charge clients, and what the conditions of employment would be for employees.

This created a uniform approach that saw each office function in a similar manner, and support each other.

“I retired in 1994 but stayed on at the Board until 1998. I would like to think that part of the success has been due to the leadership of the company, and being heavily involved in all aspects of the work.”

Norman believes a CEO is responsible for the culture, and therefore success, of a business.

“I always believed that the CEO has to lead from the front. You set the agenda, you set the strategy, the aims, the ambitions that you’re looking for and your business is to make certain that others follow,“ says Norman.

I think there’s no doubt that NDY has made a significant contribution to the air conditioning industry over many years. I am particularly proud of the quality of the young engineers, draftsmen and draftswomen that we produced, and the reputation which we gained for this work.

“I consider myself extremely fortunate that I had a close knit team around me, totally dedicated and prepared to put body and soul into every project. NDY’s current standing came out of that team effort and it’s not just one or two, it was the whole team really pulling behind the whole thing. I was very honoured to have built and led this firm from such humble beginnings.”

Special thanks to former NDY Director, Ashak Nathwani, for his contribution to this narrative and interview of David Norman.